Individual-level Strategies

Overall Goal: Develop and Implement a Campus-wide System to Screen, Identify, and Intervene with Students who are at Risk for Alcohol-related Problems

One of the most critical components of a campus strategic plan to address college student drinking is the design and implementation of a system by which college students who are at varying levels of risk get the appropriate level of services. Research tells us that college students who need services rarely get them.3 This is due in part to the low self-recognition of problems among students, as well as the lack of campus resources to screen students and to provide services.

One of the most critical components of a campus strategic plan to address college student drinking is the design and implementation of a system by which college students who are at varying levels of risk get the appropriate level of services. Research tells us that college students who need services rarely get them.3 This is due in part to the low self-recognition of problems among students, as well as the lack of campus resources to screen students and to provide services.

The first part of such a system is understanding the population of students with respect to their drinking patterns. A campus needs to be proactive and systematic about identifying at-risk students by screening in many different settings. The second part of the system is a plan to route students with different drinking patterns toward an appropriate level of intervention and monitor their outcomes. How frequently a student with an alcohol problem receives such interventions should be ideally tailored to the level of severity of their problem, but it is understood that there are constraints on resources that might make the ideal scenario unrealistic. Colleges should, at the very least, form relationships with providers in the community that can offer more intensive services to students with the highest level of problems. Referrals can then be made to these providers.

Overview

The first part of this section describes the various approaches that can be used to change individuals’ drinking behavior, followed by educational approaches that can be used to increase knowledge about risks.

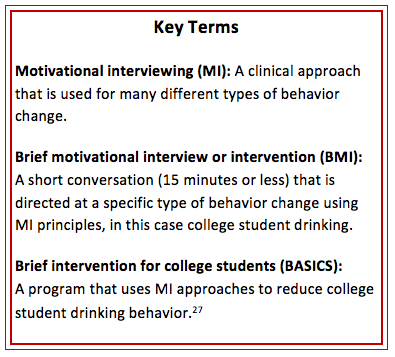

It is important to note the difference between the goals of interventions and education. While education can increase knowledge or raise awareness, research has shown that it is not effective in changing individual behavior. Behavior change is a much more difficult challenge and requires more intensive efforts like motivational interviewing (MI) and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

INVISIBLE - DO NOT DELETE

Overview ... continued

In the next part of this section, the various settings and contexts in which students can be identified and screened for high-risk drinking behavior are described. There are multiple settings in which students can be identified. Because many students will enter college with high-risk drinking patterns that began during high school, screening of first-year students is necessary to identify the students at highest risk for alcohol problems. However, because high-risk drinking can occur throughout young adulthood, opportunities for screening and interventions for students in all stages of their college career should be provided.

Students might also be identified as potentially high-risk drinkers because they violated a campus alcohol policy. For these students, strategies should be in place to identify the severity of their drinking problem before deciding on a course of action for the student. Evaluating their risk for recidivism is an important component in deciding the frequency of monitoring that might be necessary. The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) has useful guidelines for clinicians that can be found here.

Primary health care settings offer two more opportunities for screening and intervention. Students seeking routine care can be screened for high-risk drinking as well as students who present with a problem that is more directly related to excessive drinking (e.g., alcohol-related injuries). Because of the known relationship between excessive drinking and academic performance,18,19 students who are mandated to receive services from the academic assistance center or who voluntarily seek services are also candidates for screening.

Athletic programs, fraternities, and sororities offer yet additional opportunities to screen and identify students with alcohol problems. It is fully recognized that each college will vary significantly with respect to the number and types of settings in which students can be realistically identified. For example, many schools do not have a Greek system, and many two-year schools do not have health centers, so therefore the material on these settings might not be applicable to them.

This Guide also describes how faculty, resident advisors, and students can be made aware of their role in the “routing process”—that is, to simply identify, approach, and facilitate referrals to appropriate places on campus for further screening and evaluation. These individuals can be empowered and supported in an ongoing way to play this important role.

Schools vary significantly with respect to their ability to triage high-risk cases to appropriate levels of services. Ideally, a college should try to identify not only students who are exhibiting obvious signs of risky behaviors, but also those who might be at risk for developing alcohol problems. Moreover, individual-based strategies might have limited success if the individual is placed back into the same high-risk environment from which they came. Therefore, more general population-based strategies are also needed to address campus alcohol problems.

Another common finding is that short-term gains do not necessarily translate into long-term changes in behavior, unless the intervention is sustained. This can be frustrating to clinical professionals, but it makes sense if one realizes that excessive drinking is a well-established habit for many students, one that is difficult to change. Just like weight loss involves a change in the way a person identifies with food and requires ongoing vigilance, reductions in drinking behavior will require intensive and long-term monitoring.

These kinds of long-term continuous strategies to monitor alcohol use might be cost-prohibitive for schools to implement, especially if they involve regular meetings with a highly trained professional. Although long-term research studies have not been conducted among college students to determine the effectiveness of recording one’s drinking with a drinking diary or calendar, these low-cost methods have shown promise in other populations and therefore should be considered as potential strategies to reduce excessive drinking.

Research-based interventions that are designed to reduce individual behavior cannot be seen as a magic bullet, especially given the modest, albeit statistically significant, reductions that have been observed in research studies. Individually-targeted interventions by themselves are unlikely to lead to the kind of sustained changes at the population level that most colleges and communities would define as success. They need to be coupled with effective environmental strategies for multilevel, multi-component interventions.

Step 1. Choose a Screening Instrument

To estimate the level of alcohol consumed, standard assessments inquire about both quantity (the amount of alcohol) and frequency (how often one drinks alcohol). An example of a question that assesses quantity is “How many drinks do you consume during a typical weekend day?” An example of a question that assesses frequency is “How many days during the past month did you drink alcohol?” It is preferable to ask questions about how much or how often someone drinks rather than a simple yes or no question such as “Do you drink alcohol?” With yes or no questions, the person might choose to avoid any follow-up conversation by simply saying no. Questions that assume a person drinks, such as the quantity and frequency questions mentioned above, can therefore enhance honesty. Non-drinkers can simply say “I don’t drink” or “None.” A third dimension of screening focuses on the consequences that one has experienced as a result of their drinking. It is preferable to not label these consequences as “problems,” since many students will not necessarily recognize consequences as problems. The federally-sponsored National Survey on Drug Use and Health20 contains questions that measure alcohol abuse and dependence according to standard psychiatric criteria.21

There are a number of scientifically-validated screening instruments that can be easily used in college settings.22 Winters et al.22 found that the CAGE questionnaire23 was most frequently used for college settings. Other commonly used instruments among the college population are the AUDIT7 and the CRAFFT.24 Cook et al.25 found that the AUDIT, which contains ten items, was more effective than the CAGE and the CRAFFT in detecting alcohol use disorder among young adults. DeMartini and Carey26 found that the shortened form of the AUDIT that contains three items, the AUDIT-C, performed even better than the AUDIT in detecting alcohol use disorder among college students.

It is important for schools to decide on the purposes of screening before choosing a screening tool. Is the screening tool simply used to identify students who need more comprehensive assessment? In that case, it might be necessary to have a brief screening tool that separates current drinkers from non-drinkers. Although it is understandable that schools would prefer to use a screening instrument with the fewest number of items, obtaining comprehensive information about the student’s problem is a critical first step in understanding how best to intervene. Therefore, the value of a longer screening instrument should not be discounted if it will help achieve the goals of screening. Also, screening tools can be made widely available online for self-assessments or for peers to assess a potential problem in a friend.

Step 2: Implement a System to Screen and Identify Students

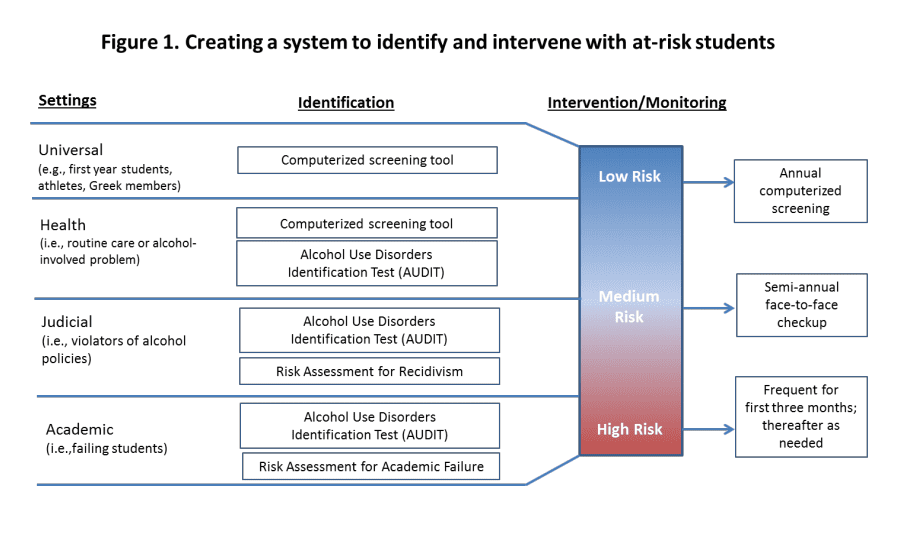

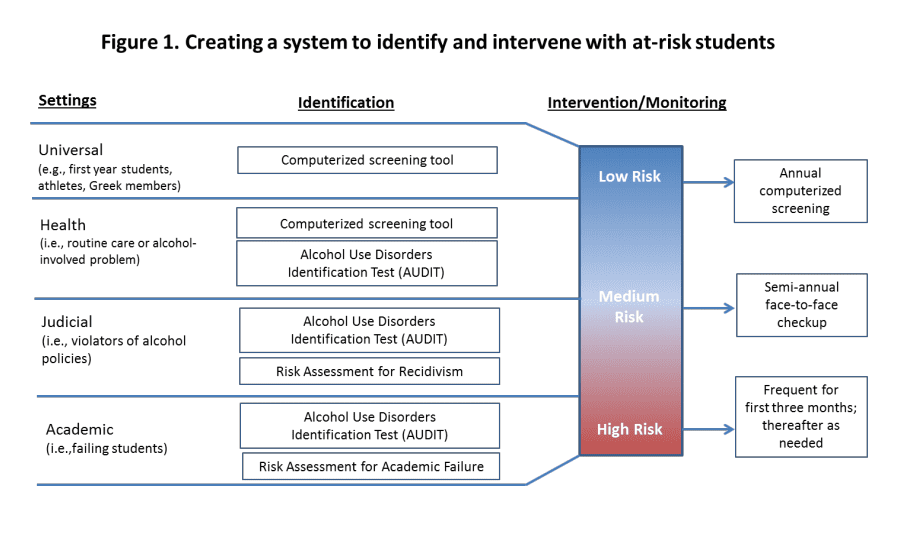

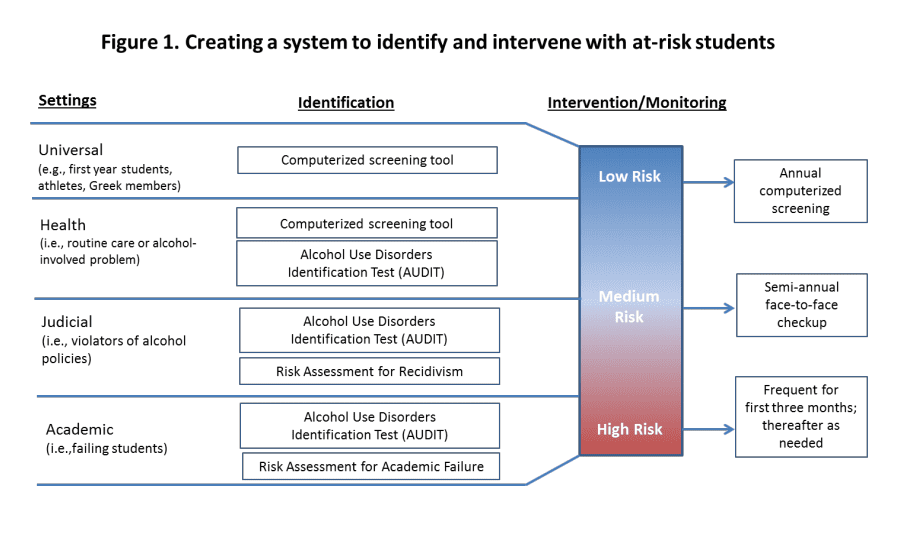

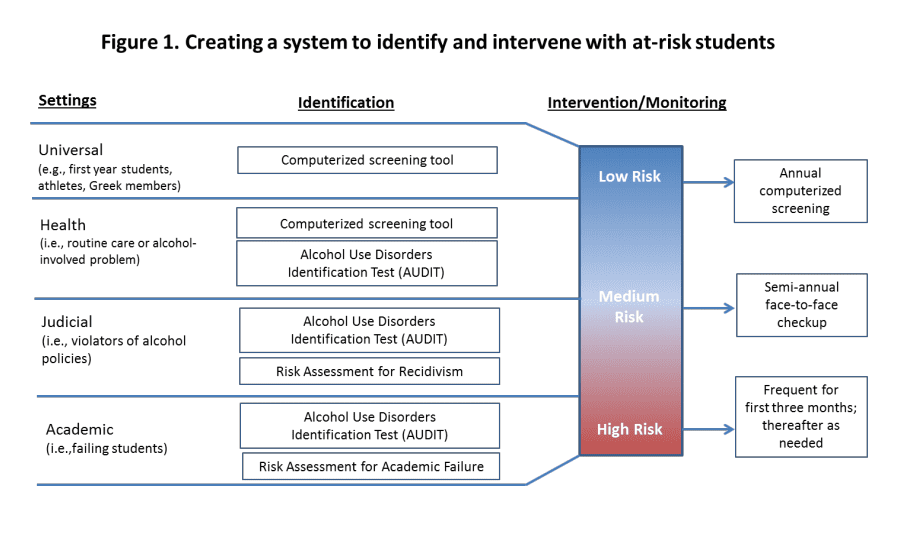

As mentioned earlier in the section on developing a strategic plan, it is important for campuses to design a “roadmap” to identify, screen, and refer students for appropriate levels of care that is tailored to their campus’s resources and needs. Figure 1 is a comprehensive example of a roadmap, with hypothetical suggestions for how often different types of students would be monitored for follow-up. This Guide describes a number of settings in which screenings can be implemented.

Step 3: Develop Criteria for Directing Students to Appropriate Resources

As can be seen in the model displayed in Figure 1, students are classified into three categories (low, medium, and high risk) based on the results of their screening. Although the screening instruments themselves provide such guidelines, the number of students falling into a high-risk category might overwhelm the resources for a particular campus, and thus schools will need to decide what those cut-points are and how students with different levels of need are routed to different levels of interventions or given referrals to additional resources.

Step 4: Monitor Student Progress

Step 4: Monitor Student Progress

Ideally, schools should monitor two features of this system. First, it is necessary to monitor the implementation of the system. For example, it is important to know what proportion of students coming through the health center were screened, and what proportion of students who screened positive were given a more extensive assessment and/or referred for an intervention. Studies have shown that performance measurement systems can be very helpful in increasing the effectiveness of interventions over time. It might not be realistic, especially if the system is new, to expect that every student will be tracked through all settings and monitored for progress, but designing a plan for measuring even a subset of students and slowly expanding it over time is essential. Second, monitoring of individual student progress can be accomplished through a variety of mechanisms using technology as appropriate.

Step 1. Choose a Screening Instrument

To estimate the level of alcohol consumed, standard assessments inquire about both quantity (the amount of alcohol) and frequency (how often one drinks alcohol). An example of a question that assesses quantity is “How many drinks do you consume during a typical weekend day?” An example of a question that assesses frequency is “How many days during the past month did you drink alcohol?” It is preferable to ask questions about how much or how often someone drinks rather than a simple yes or no question such as “Do you drink alcohol?” With yes or no questions, the person might choose to avoid any follow-up conversation by simply saying no. Questions that assume a person drinks, such as the quantity and frequency questions mentioned above, can therefore enhance honesty. Non-drinkers can simply say “I don’t drink” or “None.” A third dimension of screening focuses on the consequences that one has experienced as a result of their drinking. It is preferable to not label these consequences as “problems,” since many students will not necessarily recognize consequences as problems. The federally-sponsored National Survey on Drug Use and Health20 contains questions that measure alcohol abuse and dependence according to standard psychiatric criteria.21

There are a number of scientifically-validated screening instruments that can be easily used in college settings.22 Winters et al.22 found that the CAGE questionnaire23 was most frequently used for college settings. Other commonly used instruments among the college population are the AUDIT7 and the CRAFFT.24 Cook et al.25 found that the AUDIT, which contains ten items, was more effective than the CAGE and the CRAFFT in detecting alcohol use disorder among young adults. DeMartini and Carey26 found that the shortened form of the AUDIT that contains three items, the AUDIT-C, performed even better than the AUDIT in detecting alcohol use disorder among college students.

It is important for schools to decide on the purposes of screening before choosing a screening tool. Is the screening tool simply used to identify students who need more comprehensive assessment? In that case, it might be necessary to have a brief screening tool that separates current drinkers from non-drinkers. Although it is understandable that schools would prefer to use a screening instrument with the fewest number of items, obtaining comprehensive information about the student’s problem is a critical first step in understanding how best to intervene. Therefore, the value of a longer screening instrument should not be discounted if it will help achieve the goals of screening. Also, screening tools can be made widely available online for self-assessments or for peers to assess a potential problem in a friend.

Step 2: Implement a System to Screen and Identify Students

As mentioned earlier in the section on developing a strategic plan, it is important for campuses to design a “roadmap” to identify, screen, and refer students for appropriate levels of care that is tailored to their campus’s resources and needs. Figure 1 is a comprehensive example of a roadmap, with hypothetical suggestions for how often different types of students would be monitored for follow-up. This Guide describes a number of settings in which screenings can be implemented.

Step 3: Develop Criteria for Directing Students to Appropriate Resources

As can be seen in the model displayed in Figure 1, students are classified into three categories (low, medium, and high risk) based on the results of their screening. Although the screening instruments themselves provide such guidelines, the number of students falling into a high-risk category might overwhelm the resources for a particular campus, and thus schools will need to decide what those cut-points are and how students with different levels of need are routed to different levels of interventions or given referrals to additional resources.

Step 4: Monitor Student Progress

Step 4: Monitor Student Progress

Ideally, schools should monitor two features of this system. First, it is necessary to monitor the implementation of the system. For example, it is important to know what proportion of students coming through the health center were screened, and what proportion of students who screened positive were given a more extensive assessment and/or referred for an intervention. Studies have shown that performance measurement systems can be very helpful in increasing the effectiveness of interventions over time. It might not be realistic, especially if the system is new, to expect that every student will be tracked through all settings and monitored for progress, but designing a plan for measuring even a subset of students and slowly expanding it over time is essential. Second, monitoring of individual student progress can be accomplished through a variety of mechanisms using technology as appropriate.

Step 2: Implement a System to Screen and Identify Students

Step 2: Implement a System to Screen and Identify Students

As mentioned earlier in the section on developing a strategic plan, it is important for campuses to design a “roadmap” to identify, screen, and refer students for appropriate levels of care that is tailored to their campus’s resources and needs. Figure 1 is a comprehensive example of a roadmap, with hypothetical suggestions for how often different types of students would be monitored for follow-up. This Guide describes a number of settings in which screenings can be implemented.

Step 3: Develop Criteria for Directing Students to Appropriate Resources

As can be seen in the model displayed in Figure 1, students are classified into three categories (low, medium, and high risk) based on the results of their screening. Although the screening instruments themselves provide such guidelines, the number of students falling into a high-risk category might overwhelm the resources for a particular campus, and thus schools will need to decide what those cut-points are and how students with different levels of need are routed to different levels of interventions or given referrals to additional resources.

Step 4: Monitor Student Progress

Step 4: Monitor Student Progress

Ideally, schools should monitor two features of this system. First, it is necessary to monitor the implementation of the system. For example, it is important to know what proportion of students coming through the health center were screened, and what proportion of students who screened positive were given a more extensive assessment and/or referred for an intervention. Studies have shown that performance measurement systems can be very helpful in increasing the effectiveness of interventions over time. It might not be realistic, especially if the system is new, to expect that every student will be tracked through all settings and monitored for progress, but designing a plan for measuring even a subset of students and slowly expanding it over time is essential. Second, monitoring of individual student progress can be accomplished through a variety of mechanisms using technology as appropriate.

Step 3: Develop Criteria for Directing Students to Appropriate Resources

As can be seen in the model displayed in Figure 1, students are classified into three categories (low, medium, and high risk) based on the results of their screening. Although the screening instruments themselves provide such guidelines, the number of students falling into a high-risk category might overwhelm the resources for a particular campus, and thus schools will need to decide what those cut-points are and how students with different levels of need are routed to different levels of interventions or given referrals to additional resources.

Step 4: Monitor Student Progress

Step 4: Monitor Student Progress

Ideally, schools should monitor two features of this system. First, it is necessary to monitor the implementation of the system. For example, it is important to know what proportion of students coming through the health center were screened, and what proportion of students who screened positive were given a more extensive assessment and/or referred for an intervention. Studies have shown that performance measurement systems can be very helpful in increasing the effectiveness of interventions over time. It might not be realistic, especially if the system is new, to expect that every student will be tracked through all settings and monitored for progress, but designing a plan for measuring even a subset of students and slowly expanding it over time is essential. Second, monitoring of individual student progress can be accomplished through a variety of mechanisms using technology as appropriate.

Approaches

INVISIBLE - DO NOT DELETE

Strategy: Utilizing Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Theory Behind the Strategy

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is grounded in the idea that thoughts play a central role in behavior. It is a general clinical strategy that teaches skills to modify one’s beliefs. Working with a clinician, a student begins to understand how s/he might be relying too much on assuming things rather than carefully evaluating whether or not something is true. By identifying “automatic thinking errors,” the student can then begin to change the way they are thinking about something and subsequently change their behavior as a result. For example, a student might be thinking that drinking alcohol is necessary to reduce stress or to feel more socially comfortable. By questioning these sorts of assumptions, a student can change his/her drinking behavior.

Evidence of Effectiveness

There is a wealth of scientific evidence supporting the use of CBT for a variety of psychiatric disorders, including substance abuse and dependence. If applied with fidelity in a sufficient number of sessions, CBT is considered to be one of the most effective counseling strategies for changing behavior. In a college setting, however, single sessions might be more feasible than multiple sessions. Samson and Tanner-Smith28 reviewed evidence on various single-session intervention approaches for heavy-drinking college students, including CBT, educational approaches, motivational interviewing, and personalized feedback. Effect sizes for interventions using CBT were not significant, and the authors concluded that findings were inconclusive due to a large standard error, possibly because of variation in how it was implemented in the individual research studies. Thus, CBT appears to be better suited for students with alcohol dependence because of its more intensive multiple-session approach, whereas a single session intervention might be more appropriate for students who are at risk for developing dependence.

Tips for Implementation

As stated previously, students at the highest level of severity of drinking problems are most appropriate for CBT. CBT is best applied in clinical settings with health professionals who have received special training. If resources allow, schools can have a number of staff trained in CBT for the most severe cases, but also have referrals to others in the community who are extensively trained and provide CBT services. Interventions utilizing motivational interviewing, which are described next, can be used for students whose drinking problems are not as severe.

Strategy: Utilize Motivational Interviewing

Theory Behind the Strategy

Motivational interviewing (MI) in a college setting can be viewed as a “collaborative conversation” between a student and a health professional. The goal is to identify and capitalize on the student’s ambivalence about their drinking behavior. By listening very carefully to how a student describes his/her drinking behavior, a clinician can reflect the student’s own words to elicit internal motivations to change behavior. Alcohol use is assessed with nonjudgmental feedback, and then the clinician provides suggestions for behavioral options without confrontation.29

MI is based on three core assumptions: 1) the individual is ambivalent about the need to change his or her drinking behavior; 2) risk or harm reduction is more acceptable to the person than abstinence; and 3) students have the motivation and the skills to use drinking reduction strategies.30 Among college students, MI is generally used in the context of a brief motivational intervention (BMI). BMIs can be a one-on-one session between the student and a counselor or a computer program. They generally last for one hour or less. BMIs often assess the student’s drinking patterns to construct a personal drinking profile (e.g., quantity-frequency consumed, peak blood alcohol level, amount of money spent on alcohol, caloric intake), and then engages the student in a normative comparison exercise (e.g., beliefs about peers’ drinking, amount consumed in relation to peers) while using a non-confrontational MI style.

Evidence of Effectiveness

There is a wealth of scientific studies that support MI to change behavior, many of which have been conducted with college students. MI can effectively reduce both alcohol and drug use,31 as well as negative consequences such as blackouts.32 Many factors influence the impact of this intervention, including the number of sessions, the type of training that the interviewer has received, and whether there are continued follow-ups. The aforementioned meta-analysis by Samson and Tanner-Smith28 found that interventions using MI approaches had the most impact on alcohol use behaviors. Multiple studies show that MI appears to be effective when used alone, compared with other interventions like CBT, psychoeducational therapy, or none at all.28,33

Individual skills-based or motivational enhancement interventions might be as effective in changing college students’ drinking behaviors when the interventions are provided by trained peer counselors as when they are provided by professionals, although the professionals might be more knowledgeable and have better skills.34,35

Research has shown that face-to-face interventions are more effective when they include personalized feedback, discussion of risks and problems, normative comparisons, moderation strategies, challenging positive alcohol expectancies, and blood alcohol concentration (BAC) education.36

BMI has been identified as a potential method to cut down drinking among college students.29 A review by Carey et al.36 found that face-to-face interventions were more effective at producing changes that were maintained at long-term follow-ups than computer-delivered interventions for college drinkers. Although computer-delivered interventions were associated with decreases in alcohol quantity and frequency, these decreases were limited to short-term follow-ups and were not maintained in the long-term.

Borsari and Carey29 looked at the effects of a an intervention program based in MI principles (see Strategy: Utilize the BASICS Program) with students who reported binge drinking at least twice during the past 30 days. The intervention provided students with feedback on five components: personal consumption, perceived drinking norms, alcohol-related problems, related harms situations associated with heavy drinking, and alcohol expectancies. At six weeks, the intervention participants exhibited significant reductions in the number of drinks consumed per week, number of times drinking alcohol during the past month, and frequency of binge drinking during the past month compared with the control group.

Tips for Implementation

It is important for professionals who deliver brief interventions to think creatively about how they can optimally “connect” with a student in order to motivate them to change the way s/he views alcohol as a part of their life. MI is an intervention with guiding principles, and the professional has discretion regarding the types of alcohol-related consequences highlighted with any one particular student. The intervention will be enhanced to the degree that the professional can help the student draw connections between his/her behavior and the achievement of a goal with particular salience to that individual. Likewise, clinicians have discretion with respect to the type of guidance they provide regarding setting individual goals for reducing drinking behavior. For instance, a short-term goal might be to increase the number of abstinent days during the coming month and to monitor one’s progress toward that goal with an electronic diary.

MI includes incorporating personalized feedback and decisional balance exercises. The research evidence related to these components is described below.

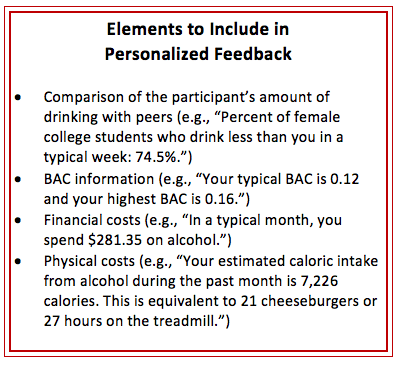

Incorporation of Personalized Feedback

Personalized feedback can be generated based on a discussion during an in-person intervention. This feedback can then be reviewed with the counselor or given to the student to take home. Alternatively, students can complete a screening program on the computer, which then provides a personalized feedback for the student to review. A counselor or physician can then meet with the student to review the personalized feedback, often using the principles of MI.

Evidence of Effectiveness

Doumas et al.37 found that counselor-guided personalized feedback was more effective than self-reviewed personalized feedback at decreasing the mean number of drinks per week and binge drinking episodes during the past two weeks. For example, mandated students who completed a counselor-guided web-based feedback intervention reduced their weekly drinking quantity by about 17% at follow-up, or an average of two drinks per week. Students who completed a self-guided

web-based intervention increased use by about 34%, or three drinks per week. A subsequent study by Doumas et al.38 found that first-year college students who completed a web-based personalized feedback program had fewer sanctions for campus alcohol policy violations compared with an assessment-only control group.

Face-to-face personalized feedback significantly reduced weekly drinking quantity and peak blood alcohol concentration in an intervention among high-risk drinking college students.39 In that study, a computer-delivered personalized feedback intervention with a video interviewer was not associated with significant reductions in drinking. Another study of incoming freshmen found that a computer-delivered personalized feedback-only program was more effective at reducing alcohol use than personalized feedback that included descriptive social norms, although both programs were effective overall.40

Using Decisional Balance Exercises

Decisional balance exercises can be done with or without the assistance of a counselor. Students are asked to write down the pros and cons of changing and not changing their drinking behavior and evaluate their motivation to change.41

Evidence of Effectiveness

Carey et al.36 found that decisional balance exercises were not effective components of either face-to-face or computer-delivered interventions targeted at college students. Specifically, face-to-face interventions that included decisional balance exercises were less effective at reducing quantity of alcohol use than interventions that did not include an exercise, though authors caution that this finding was based on few studies and future research is needed to determine if the approach is ineffective. Participants who received computer-based interventions using decisional balance exercises were less likely to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed both per week/month and per drinking day. Collins et al.42 examined students engaged in decisional balance exercises around current drinking and movement towards reducing drinking. Intervention participants included at-risk students (engaged in weekly, heavy episodic drinking) who participated in a decisional balance worksheet, brief intervention, and various assessment conditions. Decisional balance proportion (which reflected movement toward change) scores reflected greater movement towards change, which in turn best predicted reductions in heavy drinking quantity and frequency as well as alcohol-related consequences.42 While these effects decayed by the 12-month follow-up, the study suggests that decisional balance proportions are a possible measure of motivation to reduce drinking and related harms. A related qualitative study found that a worksheet with an open-ended decisional balance exercise might be better suited for college students than worksheets using Likert-scale questions because it is more personalized and a more accurate representation of what college students actually find to be beneficial or not in changing their drinking habits.43

Strategy: Utilize the BASICS Program

Theory Behind the Strategy

The Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS) program follows a harm reduction approach using MI techniques. BASICS aims to motivate students to reduce alcohol use in order to decrease the negative consequences of drinking.

BASICS is a program that is conducted during a period of two 50- to 60-minute sessions.27 These sessions include an assessment (or self-report survey) in which the student provides information about his/her current and past alcohol use and attitudes toward alcohol. This assessment information is used to provide personalized feedback around ways to minimize future risk and options for behavior change. The personalized feedback often includes clarifying perceived risks and benefits of alcohol use and comparisons of personal alcohol use to campus- and gender-specific norms. A web program based on BASICS, MyStudentBody.com, has also been developed.

Evidence of Effectiveness

Several studies have shown that high-risk drinkers participating in BASICS reduce the amount they drink significantly both in the short and intermediate term following intervention.29,44,45 A study by Borsari and Carey29 found that compared with the control group, students receiving BASICS drank fewer drinks per week, drank less frequently during the past month, and reduced the frequency of binge drinking during the past month. The number of drinks per week decreased from 17.6 at baseline to 11.4 at follow-up for the intervention group, at the same time that it fell from 18.6 to 15.8 for students in the control group. Drinking occasions per month decreased from 4.4 to 3.8 while the controls remained stable (4.5 to 4.6). Heavy episodic drinking occasions per month decreased for the intervention group from 3.2 to 2.6 and for the controls, from 3.5 to 3.4. A meta-analysis by Carey et al.46 found that BASICS was effective in reducing alcohol-related risks in the short term among mandated students who violated alcohol policies. Terlecki et al.47 conducted the first randomized trial to determine whether the BASICS program was as effective at one year post-intervention for heavy-drinking undergraduates who were mandated to complete the intervention versus heavy-drinking undergraduates who volunteered to participate. They found that the students receiving the BASICS intervention—regardless of whether they were mandated or volunteered–showed significantly fewer alcohol-related problems one-year post-intervention compared with an assessment-only control group.

Strategy: Utilize eCHUG (eCHECKUP TO GO)

Theory Behind the Strategy

The eCHECKUP TO GO program (informally known as eCHUG) is a personalized, online prevention intervention that has separate curricula to address alcohol and marijuana use as well as other health behaviors. Based on MI and social norms theory, this program is designed to motivate individuals to reduce their use using personalized information about their own substance use and risk factors associated with use. eCHUG is individually tailored to each campus and can be shared school-wide among departments.

eCHUG is self-guided and takes about 20 to 30 minutes to complete. Students can complete a personal check-up on multiple occasions to track changes about their use and risk behaviors. If a counselor wishes to use the program in conjunction with face-to-face contact, the student can be asked to complete the companion Personal Reflections program. This feature requires an additional 15 to 20 minutes and asks students to respond to questions designed to further examine their personal choices and the social norms surrounding and influencing their use of substances.

Evidence of Effectiveness

Two research studies compared alcohol outcomes between first-year students receiving eCHUG and an assessment-only control group. Both of these studies showed a significant reduction in the mean number of drinks per week for students who received eCHUG. One study48 found a reduction of 1.43 (with an increase of 6.33 for the control group) at one month post-intervention. The other study, by Doumas et al.,49 observed a decrease in mean number of drinks per week of 0.6 at three months post-intervention, as compared with an increase of 0.3 for the control.

Another study tested the effectiveness of eCHUG among first-year students when added to existing alcohol education programs (Alcohol 101 and CHOICES).50 The four intervention groups included: 1) Alcohol 101 + eCHUG, 2) Alcohol 101 alone, 3) CHOICES + eCHUG, and 4) CHOICES alone. Those in the combined eCHUG conditions reported consuming fewer drinks per hour (an average of 0.4 drinks) compared with curriculum conditions without eCHUG (an average of 1.3 drinks) at a four-week follow-up. This study did not have a control group, so researchers were not able to conclude that eCHUG is effective as a stand-alone intervention for this population; rather, beneficial effects might result when it is used in combination with other education programs.

eCHUG has been found to be more effective among heavier drinkers than lighter drinkers, according to a study that compared eCHUG with a control condition among first-year students.51 Among mandated students, another study found that eCHUG did not significantly decrease alcohol use when compared with BASICS and CHOICES, but it did significantly decrease alcohol-related harms.52

One study compared the drinking behavior of mandated students who received eCHUG with either self-guided feedback versus counselor-delivered feedback.53 Students who received eCHUG with self-guided feedback reduced their drinking by about one drink per week. In comparison, students who received counselor-guided feedback saw a decrease of about four drinks per week, suggesting that eCHUG might work best when in conjunction with other treatment and prevention methods.

Strategy: Challenge Alcohol Expectancies

Theory Behind the Strategy

Many college students are under the impression that alcohol use carries with it a number of social benefits, including an increased sense of well-being and relaxation, being more socially comfortable, and feeling more attractive. What is not clearly understood is that the “placebo effect” for alcohol is very strong. A wealth of research shows that individuals who believe they are drinking alcohol but actually receive a non-alcoholic drink will report the same positive benefits from drinking. Alcohol expectancy challenge (AEC) programs “challenge” these assumptions about drinking.54-56

Evidence of Effectiveness

Scott-Sheldon et al.57 reviewed the evidence around interventions targeting alcohol use among college students. They found that behavioral interventions during the first year of college that include an AEC were more effective in reducing drinking and harms among college students than those that did not include it. One study compared the drinking behavior of college students assigned to an AEC or a control group.54 Using the Alcohol Expectancy Questionnaire (AEQ) to measure beliefs about outcomes of alcohol use, the researchers showed that the perceived positive effects of alcohol were decreased in the experimental group as compared with controls. Wood et al.56 found that effects lasted three months post-intervention but decayed by six months.

Statmates et al.58 examined the relationship between individuals who were first intoxicated earlier in life and alcohol expectancies. More experienced drinkers were found to have stronger beliefs related to drinking which influenced their drinking behaviors and willingness to change. Madson et al.59 investigated the impact of protective behavioral strategies with an AEC. Among females, but not males, protective behavioral strategies mediated the relationship between positive expectations and drinking quantity.

Another study randomly assigned participants to one of four conditions: BMI, AEC, BMI and AEC combined, and an assessment-only control group.56 While BMI produced significant decreases among all variables, AEC produced significant decreases in measures of total drinks during the past 30 days and frequency of heavy episodic drinking during the past 30 days. AEC conditions showed an increase in intervention effects after three months, but these gains declined completely after six months. This study shows the effectiveness of AEC in the short term but demonstrates the need for it to be accompanied by passive booster sessions.

Tips on Implementation

AEC programs can be implemented in a variety of ways. One prime example is that of a social setting where alcohol and a placebo drink are given to participants in combination with information and education regarding placebo effects.60-62 These types of programs can be implemented in various settings, including residence halls, first-year orientation, and campus organization events.63 Due to the fact that these programs are only effective in the short run, they can be targeted to specific periods of time where alcohol use among the student population might be high (i.e., rush week or spring break).

Strategy: Combine Alcohol and Sexual Assault Prevention

Theory Behind the Strategy

Sexual assault is a serious public health concern, and can be a risk factor for experiencing depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, as well as academic performance problems.64,65 It is estimated that about 20% of women and 6% of men experience some form of sexual assault during their four years in college (although some sources estimate it to be higher among women), with the highest probability of assault during their first two years.66

Reducing excessive drinking as described throughout this Guide should be considered as part of an overall comprehensive sexual assault prevention strategy for college campuses. Alcohol, while never a cause of sexual assault, can be a major contributing factor. Alcohol use by the victim, perpetrator, or both is estimated to be involved in about half of all campus sexual assaults.67-70 Alcohol impairs judgement, dulls senses, slows reflexes, and lowers inhibitions, which has implications not only for victims but perpetrators and bystanders71-74; this makes a sexual assault more likely to happen and less likely to be stopped.

It is important to realize that regardless of whether or not alcohol was involved, victims of sexual assault should be provided the services that they need to manage the aftermath of the trauma experienced. One study found that after a sexual assault in which the victim had consumed alcohol prior to the incident, there was an increased likelihood for alcohol abuse as a means to cope, thus creating a cyclical relationship which puts victims at greater risk for unsafe drinking behaviors and other negative consequences.75

Evidence of Effectiveness

Senn et al.76 conducted an intervention designed to provide college women with strategies to avoid rape at three Canadian universities. The intervention consisted of four three-hour sessions of lectures, games, facilitated discussion, practice activities, and included specific components on excessive drinking.73 The control group received pamphlets about sexual assault, which was the existing practice at the participating universities. After one year, the women who received the intervention experienced a completed rape at about half the rate of the control group (5.2% versus 9.8%), as well as significantly lower rates of attempted rape (3.4% versus 9.3%). Women in the control group who reported being previously victimized had a risk for completed rape that was nearly four times greater than women who had not been previously victimized.

Gilmore et al.77 studied the effectiveness of a web-based program that combined sexual assault prevention and alcohol reduction strategies among college women at high risk for victimization, based on drinking behavior. The combined approach reduced the number of incapacitated rapes, incidence of sexual assault and severity, and frequency of heavy episodic drinking among individuals with a more severe victimization history.

Tips on Implementation

The findings of Senn et al.76 and Gilmore et al.77 are extremely promising, but more research is needed to better understand how alcohol can make a person more susceptible to sexual victimization and how reducing alcohol use should be factored into sexual assault prevention programs on campuses. Certainly, colleges should aim to eliminate stigma related to alcohol-related sexual victimization in order to support victims. Moreover, interventions to reduce excessive drinking should be developed and evaluated as a way to prevent perpetration and improve the capacity of bystanders to effectively intervene. In 2016, Maryland Collaborative staff produced an evidence review summarizing the research on the complex relationship between alcohol and sexual assault on college campuses. This review can be used by educators, administrators, and students as an informational resource as they develop sexual assault prevention programs or activities on campus.[

Educational Approaches

Research studies have consistently demonstrated that while education can increase awareness of alcohol problems and knowledge of alcohol-related risks, it generally does not result in changing behavior. Therefore, universities should not expect that education programs alone will reduce alcohol use or related problems. Educational approaches can assist in increasing awareness of and supporting other types of strategies, such as policy changes or implementation of screening, brief interventions, and referral to treatment.

INVISIBLE - DO NOT DELETE

Strategy: Educate Students about the Dangers of Excessive Drinking

Theory Behind the Strategy

The theory behind educational approaches is that students will be less likely to engage in heavy drinking if they are more aware of the risks involved. Unfortunately, this notion has not been borne out by many years of prevention practice and research. New neurobiological research has shed light on the fact that many college students are developmentally-wired for risk taking and therefore simply educating them about risks will not change their behavior. Some college students have a low level of risk-taking tendencies and might be more susceptible to messages about risk; however, risk-averse students are likely already engaging in heavy drinking.

Evidence of Effectiveness

Alcohol education has very little impact on changing behavior and is not effective as a stand-alone intervention.78 Alcohol education is often used as a control condition in research studies, further highlighting its ineffectiveness as an alcohol reduction strategy. However, it can be incorporated into interventions that include other elements. One study used a mixed-methods approach to evaluate an alcohol education program for use among fraternity members.79 The alcohol education program under study, the Alcohol Skills Training Program, was not found to be effective among this group. Certain components of the program were viewed as useful by the participants, but this did not translate to significant differences in high-risk drinking behavior or negative consequences between test and control groups.

Another study tested the addition of information on alcohol use, decision making, and safety into already existing academic courses instead of making alcohol education its own course, a strategy known as “curriculum infusion.”80 The authors’ analysis found students were engaged in these lesson plans and took the material seriously, but further research is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of this strategy at decreasing alcohol use and related consequences.

Tips on Implementation

Alcohol education can be combined with other intervention strategies that target students who are at risk. For example, a BASICS component for students to explore their alcohol use can be implemented with additional education (either online or in-person programs). More research is needed on the effectiveness of infusing alcohol education into existing course curricula.

Strategy: Utilize Computer-facilitated Educational Approaches

AlcoholEdu

Description

AlcoholEdu for College is a two- to three-hour online alcohol prevention program developed to be made available to an entire population of students, such as an entering first-year class. Educational goals include resetting unrealistic expectations about the effects of alcohol and understanding the link between drinking and academic and personal success.

Evidence of Effectiveness

Five research studies examined alcohol-use outcomes between first-time, incoming college freshman who completed the AlcoholEdu program.48,81-84 Both the intervention and control groups experienced increases in drinking behaviors between high school and the transition to college, but students in the intervention groups had smaller increases in drinking compared with students in the control group.48,83 Significant differences between the two groups of students were found for average number of drinks per week: Hustad et al.48 found that the AlcoholEdu group had a mean increase of 1.5 drinks per week during the past month versus 6.3 drinks among the control group, while Lovecchio, Wyatt, and Dejong83 found a mean increase in total number of drinks during the past two weeks of 4.3 among the AlcoholEdu group versus 8.0 among the control group. A smaller increase was found in heavy drinking episodes per month in the intervention group (increase of 0.6 episodes48 and 19% of students83) than in the control groups (increase of 2.3 episodes48 and 34% of students83). Additionally, the intervention group in Lovecchio’s study reported fewer positive alcohol use expectancies and less acceptance of others’ alcohol use.83

AlcoholEdu also had a small but statistically significant effect on student’s knowledge about alcohol (22.7% score increase for the control condition vs. a 23.4% increase for the intervention condition, p=0.04).83 While one study82 found no significant differences between the two groups for measures of alcohol quantity, further review showed there were baseline differences in parental discussions, alcohol education during high school, and alcohol-related knowledge. Another study had mixed findings on the mediating effects on students’ perceived drinking norms, alcohol expectancies, personal approval of alcohol use, and protective behavioral strategies on the effectiveness of AlcoholEdu.84 Exposure to AlcoholEdu was inversely related to student perceptions of drinking norms, which could have decreased drinking rates and drinking related harms indirectly through changing perceptions, but it did not affect any other psychosocial norms that were targeted.84 Barry et al.81 conducted a qualitative follow-up survey two to four months post-AlcoholEdu intervention. They found an increase in knowledge about alcohol, but there was no change in alcohol-related behavior. Limitations, such as skipping through assessments and video segments without reading or listening, were also noted.

In summary, AlcoholEdu can greatly enhance students’ alcohol knowledge and use of safe drinking practices (including abstaining). However, increased knowledge does not necessarily translate into behavior change. Administrators should be wary of relying solely on this program, as its effects tend to return to baseline by the next semester.85

Tips on Implementation

Administrators who implement AlcoholEdu should consider combining this program with other prevention and intervention programs in order to have a higher magnitude of effect in the long-term. If used, AlcoholEdu should be supplemented with other strategies to screen, identify, and intervene with high-risk drinkers using appropriate and evidence-based methods.

Alcohol 101 Plus

Description

Alcohol 101 Plus is a web-based program that is based off the previous CD-ROM-based version, Alcohol 101. This psychoeducational prevention program consists of an interactive format in a “virtual campus” where the student makes choices about social situations involving alcohol, such as at a party, discusses possible consequences, and considers alternatives. Participants might also visit a “virtual bar” that provides information on their estimated blood alcohol concentration based on number of drinks consumed, weight, and other relevant factors, and can include icons that inform them about alcohol refusal skills, consequences of unsafe sex and underage drinking, comparisons of participant drinking rates with college norm rates, multiple choice games relevant to alcohol, and depictions of real-life campus tragedies involving alcohol misuse.

Evidence of Effectiveness

Four studies compared alcohol-use outcomes among students who drink following completion of the computer-based Alcohol 101 program and other in-person interventions, such as BMI, CBT, and BASICS.86-89 Participants varied between studies, categorized as either violators of alcohol policy who were mandated to complete education,86,88 high-risk drinkers seen at the health clinic,87 or participants from the general student population who reported having at least one drink during the past 30 days.89 Results showed very few advantages of Alcohol 101 interventions over other programs. Carey et al.86 found no effect at a one-month follow-up in mandated female students who completed Alcohol 101, aside from a significant reduction of 0.9 points in the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI; a 23-item screening tool for adolescent problem drinking) score, indicating a small reduction in alcohol-related problems. No reduction was found for males. This reduction was not significantly different from that of individuals in the BMI condition, who also saw a reduction in alcohol quantity, frequency, and BAC. Murphy et al.87 found an average reduction of three drinks per week, but these results were not significantly different from students who received BASICS. However, there was no assessment-only control, so the reduction might not have been an intervention effect.

Another study also found that when compared with BMI, outcomes were similar between groups; both Alcohol 101 and BMI decreased number of drinking days per month by roughly one at the three-month follow-up (1.3 and .5 drinks, respectively), then increased again by approximately 1.5 drinks at 12 months.88 The only demonstrated advantage of Alcohol 101, according to Carey et al.,86 was a decrease in alcohol-related problems, as indicated by the RAPI score. Two of the studies found a general return to baseline drinking after 12 months, despite a brief reduction in drinking at three months.86,88

Tips on Implementation

Little evidence is available that supports the effectiveness of this program to change behavior.

Alcohol-Wise

Description

Alcohol-Wise is an online alcohol abuse prevention course designed for first-year students and other high-risk groups on college campuses. The program takes between one and two hours to complete, and consists of a pre-test of alcohol knowledge, a baseline survey (modeled from eCHUG), educational lessons on alcohol, and a post-test of alcohol knowledge. Alcohol-Wise integrates personalized feedback as students navigate through the program. A baseline follow-up survey is administered about one month after course completion.

Evidence of Effectiveness

Only two studies on Alcohol-Wise were identified. The first presents findings from a randomized controlled trial of 58 undergraduate students assigned to either Alcohol-Wise or a control group.90 After one month, freshman and sophomore students had significant reductions in alcohol use and BAC, but juniors and seniors did not. No significant changes in alcohol expectancies were observed between either the intervention group or control group. The other study examined the short-term effectiveness of Alcohol-Wise among incoming first-year students at two universities.91 Both universities saw a significant increase in alcohol-related knowledge, but effects on drinking behavior were mixed: One university saw a significant reduction in alcohol use and high-risk drinking behaviors such as drinking games and heavy drinking, while the other university did not. Although the authors did not intend to directly compare the two universities, there was substantial variation between the campus types which makes it difficult to conclude whether or not Alcohol-Wise would be effective in other schools.

Settings in Which to Screen, Identify, and Intervene

INVISIBLE: DO NOT DELETE

First-year Orientation

Theory Behind the Strategy

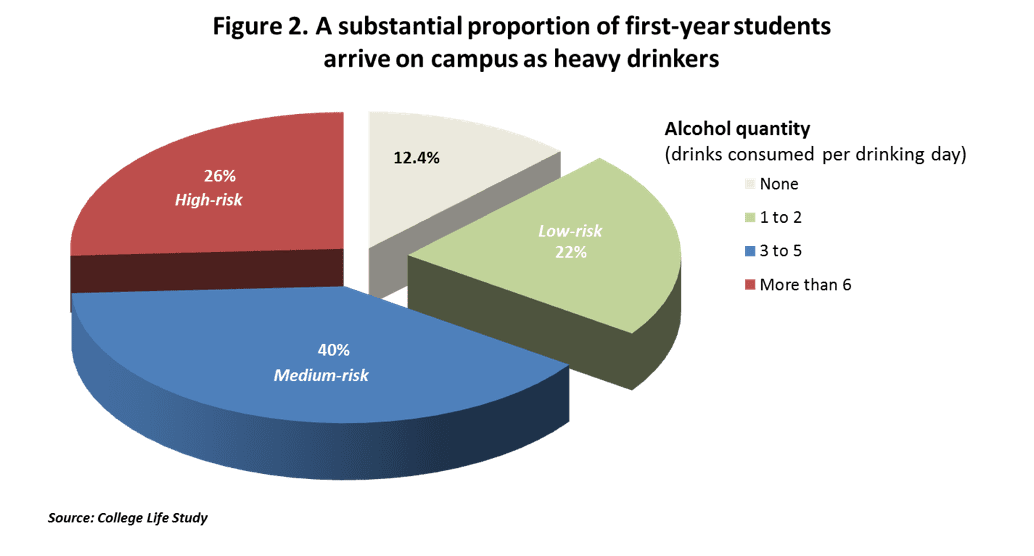

Screening at first-year orientation provides a means of identifying risky drinking practices early through large questionnaire-based screening tools that measure quantity, frequency, and consequences.35 This process can help administrators identify and subsequently refer students for appropriate help. Because some students will enter college with high-risk drinking patterns that began during high school, screening of first-year students is necessary to identify those at highest risk (see Figure 2). Universal screening might be helpful in capturing problems early among incoming students. Screening can occur during orientation or even first-year seminar

classes as a means to identify those who are high risk or have factors that place them at higher risk than others for developing a future problem (e.g., family history, high levels of risk-taking).

Evidence of Effectiveness

One longitudinal study looked at a sample of first-year students and provided confidential questionnaires as part of orientation programs conducted in each

residence hall during the first three weeks of the fall semester with additional follow-up near the end of their junior year (32 months later).92 The survey included variables on quantity and frequency measures as well as problems directly related to alcohol use. The survey also contained questions from the CAGE and the Perceived Benefit of Drinking Scale (PBDS), an index that measures adolescents’ perceived benefits of drinking.

Three categories of students were present among this sample: nondrinkers (11%), low-risk drinkers (51%), and high-risk drinkers (38%). Drinking quantity/frequency during junior year was significantly correlated with quantity/frequency at entry into college (r=0.69, p<0.01). These results support the idea of identifying adolescents at high risk for current or future drinking problems through the screening of first-year students.

Findings from a meta-analysis by Scott-Sheldon et al.57 indicated that individual and group behavioral interventions for first-year college students significantly reduced both alcohol use and problems related to alcohol use with lasting effects up to four years post-intervention. Another study looked at providing a personalized web-based feedback program (eCHUG) for students in a first-year seminar as a means to reduce heavy drinking.93

The sample consisted of low-risk and high-risk drinkers. It was found that high-risk first-year students in the eCHUG group reported a 30% reduction in weekly drinking quantity, 20% reduction in frequency of drinking to intoxication, and 30% reduction in occurrence of alcohol-related problems (as compared with 14%, 16%, and 84% increases, respectively, among the control group). The results of this study revealed that nearly half of the first-year students (41%) reported binge drinking at least once during the past two weeks, and that there was an increase in drinking through the spring for first-year students among the control group.93

Tips on Implementation

Universal screening to identify risky drinking practices early can be done in a variety of ways, and while it might be ambitious and costly (depending on campus size), it can help students access the services they might need.35 Implementing questionnaire screenings in first-year seminar courses or orientation sessions can serve as a basis for identifying potential students who might be at risk for alcohol-related problems. Screening in both the fall and spring semesters should be considered in order to identify these at-risk students.

Primary Health Care

Theory Behind the Strategy

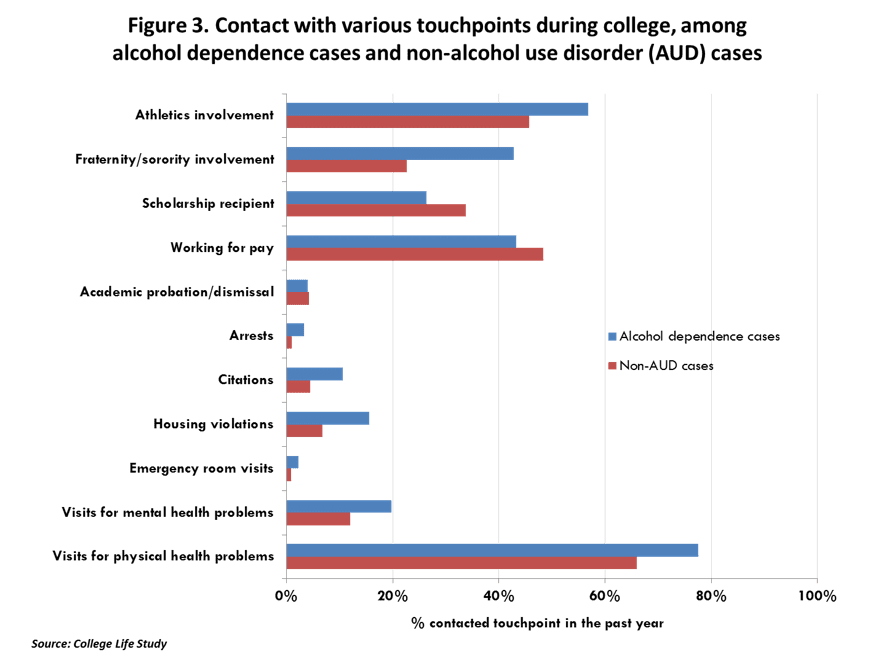

Research has demonstrated that most college students receive services from medical professionals during the course of the school year.94 Because of their frequent contact with students at risk for alcohol-related problems (see Figure 3), it might be worthwhile to train physicians and other allied health care professionals in basic techniques to ask students about their alcohol use patterns as a routine part of care, and intervene when excessive drinking is detected. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that “clinicians screen adults aged 18 years or older for alcohol misuse and provide persons engaged in risky or hazardous drinking with brief behavioral counseling interventions.”95 Integrating questions about alcohol use into routine health care visits can help reduce stigma by placing alcohol use on par with other behaviors that affect health, like eating habits and seat belt use. Alcohol use is associated with a wide range of health consequences, such as decreased immunity, sleep problems, depression, anxiety, and other mental health conditions. Thus, physicians, nurses, and other medical professionals play an important role in intervening with at-risk students if they understand the extent to which alcohol use might be a contributor to the health care complaints of the patient. Physicians and other medical professionals are in a position of professional authority and messages that they convey might be taken more seriously by patients, although this principle might not hold true in the case of young adult college students, who are more likely to be in a developmental stage where questioning authority and feeling invincible are commonplace.

Evidence of Effectiveness

Several studies have demonstrated that physician-delivered advice and brief interventions are associated with reductions in alcohol use among general patient populations. Helmkamp et al.96 demonstrated not only the feasibility of primary care screening, but also found that 96% of participants who screened positively for alcohol dependence after an emergency department visit accepted counseling during their visit. Additionally, participants indicated at follow-up that they found the counseling interventions to be helpful and displayed significantly lower AUDIT scores on all three domains: alcohol intake, alcohol-related harm, and alcohol dependence.

Specific to college students, Amaro et al.97 showed that the BASICS intervention can be delivered within the university health care center with good results; namely, it was associated with reductions in both quantity and frequency of alcohol and other drug use among participants between baseline and six-month follow-up, including a 17% decrease in their weekly heavy episodic drinking during the past month.97 Similarly, in another study of students who screened positively on AUDIT measures and received a basic intervention, drinks per week during the past 30 days were reduced by almost four, peak drinking during the past 30 days was reduced by more than one drink, and number of heavy episodic drinking occasions during the past two weeks was reduced by almost one.98 Schaus et al.99 found that students who screened positive for high-risk drinking after presenting as a new patient at a university health service, those who received a BMI and BASICS had statistically significant reductions over time in drinking behavior outcomes as compared with a control group. More specifically, use fell by an average of 2.2 drinks among the intervention group and 0.7 drinks among the control group at six-month follow-up. These studies provide evidence that interventions delivered by providers within a primary care/health center are effective in reducing negative alcohol behaviors and associated harms, especially among those who are high-risk drinkers.

Another study by Denering and Spear100 analyzed data among 18- to 24-year-olds from a college mental health clinic for routine screening and brief intervention for alcohol and drug use. A slight reduction in the prevalence of binge drinking (90.6% to 88.6% among men and 73.4% to 71.4% among women) was observed, but reductions in the frequency of binge drinking were not significant.100 Although further research is needed to support the use of routine screening in college mental health service settings, the findings from primary care settings could reasonably extend to mental health services.

Tips on Implementation

Because physicians have little time to engage in a meaningful in-depth conversation with their patients, having students complete computerized self-assessments prior to the appointment will save time and perhaps increase the veracity of the patient’s information. The report can then be transmitted to the physician immediately prior to his/her interaction with the patient.

Creating on-campus opportunities to train physicians and other health center personnel can increase the level of comfort with discussing alcohol use, as few medical schools and residency programs provide comprehensive

training on assessment and intervention of substance use. Such trainings should provide research-based information on the connection between alcohol use and several common health complaints of students to help physicians see the value of addressing alcohol use as part of their plan to improve student health.

As mentioned previously, the USPSTF published recommendations in 2013 stipulating that “clinicians screen adults aged 18 years or older for alcohol misuse and provide persons engaged in risky or hazardous drinking with brief behavioral counseling interventions to reduce alcohol misuse,” based on sufficient evidence of the benefits of this approach.95 This web resource might serve as a tool for schools to advocate screening in health centers. Some campuses might house both mental and physical health services under one center; in these environments, it is important for both sides to coordinate efforts to consistently and routinely conduct screening and brief intervention so that students who have or are at risk for alcohol problems can easily be referred to the appropriate treatment or intervention.

Students who Violate Campus Alcohol Policies

Theory Behind the Strategy

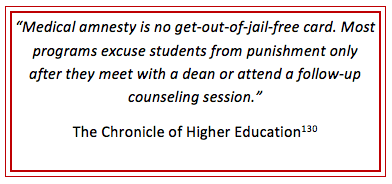

Sanctioned students who undergo a mandate for violations of campus alcohol policies and are referred for intervention can cue self-initiated reductions in drinking. Consistent enforcement of policies and sanctions for students who violate alcohol policies can lead to lower heavy drinking rates among students.86 There is general consensus of a “mandate effect”—that is, that no matter what intervention is delivered, there will be reductions in drinking simply because the student has been mandated to receive something. The important implication, therefore, for colleges, is that enforcement of policies—to achieve the goal of identifying students who are violating policies and mandate them to some kind of intervention—is crucial to reduce drinking. Being mandated should be viewed as a “teachable moment” instead of a punishment.

Evidence of Effectiveness

There is evidence to suggest that mandated interventions for students sanctioned for alcohol policies might reduce alcohol use and its consequences.86 Administering BMI with counselor-guided feedback can further reduce alcohol use and consequences. Studies that utilize a no-intervention control group are not possible for ethical reasons. Usually, a two-group or pre-post design is used. Sometimes a “delayed” control is used, consisting of mandated students who are waiting to be seen. Several research studies have evaluated the effectiveness of various types of interventions on mandated students. A 2016 meta-analysis of alcohol interventions among mandated college students found that BASICS and eCHUG were effective in reducing alcohol-related risks in the short-term.46 Terlecki et al.47 found BASICS to be effective in reducing drinking and related problems at one-year follow-up among both heavy-drinking mandated students as well as undergraduates who volunteered to participate. Another study found significant reductions in RAPI scores from baseline to three months and then again from three months to six months in BMI interventions as opposed to usual services for mandated students.101

Additionally, mandated students who received counselor-delivered personal feedback showed a nearly two-drink reduction per week at an eight-month follow-up as opposed to those who received self-guided written feedback who increased their use by almost two drinks per week at follow-up. Furthermore, although those in the counselor-delivered personal feedback group slightly increased their past-two-week heavy episodic drinking (by less than half an episode), this increase was significantly less than those who received self-guided written feedback (who added an entire additional episode per two weeks).37

Tips on Implementation

All mandated students are not the same. Some might have very serious problems and require intensive intervention. Others might present with less severe problems, and perhaps need a lower level of services, but facilitating some sort of intervention for these students is essential to reducing the likelihood that their problem will worsen. Moreover, stories of their experiences will be important for spreading the word among their peers that alcohol violations are taken seriously and result in consequences.

The first step of any mandated program should be a comprehensive assessment of drinking history, current behavior, and problems. Several instruments are available for this purpose. Detailed information about drinking history can flag individuals who are at higher risk than others. For instance, individuals who started drinking prior to age 16 or individuals with a parental history of alcoholism are at greater risk for developing alcohol problems in the future.102,103 Moreover, information should be gathered regarding current problems experienced by the student, such as academic difficulties, health problems, or feelings of depression or lack of motivation. This sort of information related to risk factors and current problems that might be associated with alcohol use can be useful to clinical staff during a brief intervention.

Students Receiving Academic Assistance

Theory Behind the Strategy

There is a strong link between excessive drinking and academic performance problems, including lower grades.18,104 Excessive drinking undermines the learning process in at least two major ways. First, simply the time spent drinking detracts from the time spent on more productive activities, such as studying. Second, students who drink excessively are more likely to skip class and might also experience concentration and memory problems associated with heavy drinking.18

Academic assistance centers typically emphasize strengthening skills that are specific to academics—especially time management and study habits—yet these skills must be applied within the context of whatever barriers to success are presented by the student’s behaviors, choices, and life circumstances. Rather than being a taboo subject that academic counselors avoid, excessive drinking should be taken into account along with other potential barriers to academic functioning such as financial hardship, family problems, and roommate problems.

Students who are receiving academic assistance have taken an important step that demonstrates openness to ameliorating the obstacles to their personal academic success—whether they were referred by someone else or themselves. These students are in a uniquely “teachable moment” with potential to stimulate self-reflection and behavior change in multiple domains of their life. Academic counselors should take advantage of this opportunity to identify students whose drinking habits might be having a negative effect on their grades and refer them as needed for a more comprehensive assessment.

Evidence of Effectiveness

At this time, few schools are implementing screening within academic assistance centers, and therefore little is known about the effectiveness of this strategy. However, to the extent that it results in more high-risk students being referred for screening and brief intervention, we are convinced that it has great potential for reducing excessive alcohol use, as well as for enhancing academic outcomes.

Tips on Implementation

Staff working in academic assistance centers could be trained to administer a simple screening instrument to students at the time of intake. Similar to health care service settings, where staff time is valuable, it might be less costly to have students complete computerized self-assessments prior to the appointment. Transmitting the report to the staff member immediately prior to the appointment might alleviate their discomfort in having to directly ask about the student’s alcohol use.

Creating on-campus opportunities to train academic assistance personnel about how to discuss alcohol use can increase their level of comfort with this sensitive topic. Training should include research-based information on the connection between alcohol use and academic performance, which will help academic counselors see the importance of addressing alcohol use as part of their plan to help the student improve his/her study habits and overall academic performance.

Athletic Programs

Theory Behind the Strategy

Athletes are at high risk for problem alcohol use and related consequences.105-108 Studies have shown that athletes consume more alcohol and experience higher rates of alcohol-related consequences as compared with their non-athlete colleagues.109 Apart from the risk for unintentional injury, alcohol use can negatively impact performance and recovery in athletes.110,111 Screening athletes in college/university athletic programs is an important means of identifying students since they are a target group for heavy drinking. Screening can take place during student-athlete orientation prior to the start of the first year with follow-up programs throughout the year. Identifying these students in this group early on can help move students to appropriate services and treatment. Coaches, team leaders, and athletic trainers are highly influential in the lives of athletes, and therefore can be important partners in programs targeting student-athletes.

Evidence of Effectiveness

A study by Doumas et al.112 compared heavy drinking and alcohol-related consequences among first-year student-athletes and non-athletes, and found that first-year athletes reported higher levels of drinking, drunkenness, and academic, interpersonal, physical, and dangerous consequences than their counterparts. Student-athletes were asked about quantity of drinking on the weekend and frequency of drunkenness, as well as alcohol-related consequences using tools like the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ) and the Young Adult Alcohol Problems Screening Test (YAAPST). It was found that athletes reported heavier drinking as compared with non-athletes in the fall that intensified in the spring term.

For student-athletes, it is important to consider the timing of strategies, as their athlete orientation programs generally occur at the beginning of each term. College administrators might want to consider providing screening and intervention programs throughout the academic year in order to provide continuous monitoring of alcohol problems among students. It is also important to consider who specifically can and will provide an intervention for student-athletes, such as coaches or athletic trainers. A recent review on alcohol-related unintentional injury among college athletes states that athletic trainers “have the capability and responsibility to play active roles as integral members of the health care team,” but lack the confidence or self-efficacy to do this.113 Intervention involving athletic trainers will require further research into how to best develop and adapt existing screening and brief interventions based on the trainer’s experience and confidence in addressing alcohol problems with student-athletes.113 Additionally, norms modeled by coaches and teammates might discourage or promote drinking; thus, taking action such as setting team policies around alcohol use could be beneficial.114

Research supports the idea that BMIs are effective in reducing heavy drinking among college students, particularly first-year student-athletes. Another study by Doumas et al.115 examined an intervention program for student-athletes as part of first-year seminar curriculum. The program implemented, eCHUG, is designed to reduce high-risk drinking through feedback and normative data around drinking and associated risks. High-risk students in the study’s intervention group reported reductions in weekly drinking (46%), frequency of drinking to intoxication (46%), and peak alcohol use (32%), compared with increases among the comparison group (21%, 6%, and 11% respectively). Since athletic staff and university personnel need to recognize that heavy drinking can progress through the year, implementing programs periodically throughout the year might be beneficial.

Tips on Implementation